933 Rochester Way, Eltham, 1936 - A Girl's Story

We all loved our house on the Rochester Way. I was so excited to move in. The estate was far from finished, many of the roads were still unmade. The garden had nothing in it apart from some fruit trees and lots of rubble. I was thrilled that we had moved in to a proper house with stairs.

We all loved our house on the Rochester Way. I was so excited to move in. The estate was far from finished, many of the roads were still unmade. The garden had nothing in it apart from some fruit trees and lots of rubble. I was thrilled that we had moved in to a proper house with stairs.

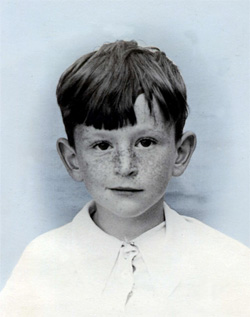

My parents had the main bedroom at the front; Peter had the small box room over the front door, and my room was at the back, overlooking the garden. The bathroom was next to my room. Peter wasn�t that pleased with his room, he wanted mine because it was bigger; but he was only a little boy, not quite 4 years old, and I was almost 9.

Downstairs was the front room which was only used on high days, holidays and of course Christmas. At the back was the dining room, with quite the latest thing � a kitchenette at one end, with a curtain across it. My mum seemed to cope in this small space. A sink and draining board under the window, a very small worktop with a cupboard underneath; a wall cupboard, a gas cooker and a copper (no washing machines then) and the door into the stair cupboard at the end, where I spent quite a bit of time for being naughty. We lived in the dining room; it had an open fireplace on one wall, with my mum and dad�s small armchairs one each side. Peter and I had a stool each to sit on in front of the fire. My dad would roast potatoes in the ashes, and make real toast with a brass toasting fork which hung on the wall by the fire. The fireplace was the focus of the room.

There was a dining room table and four chairs, and of course the radio, or as we called it, the wireless. Peter and I never missed Children�s Hour with Uncle Mac which was on every day except Sunday. We followed the adventures in Toy Town with Larry the Lamb, Ernest

Being a child in those days did have its compensations. We had much more freedom to go out to play. In the school holidays we could go out all day quite safely. We both had scooters and we went all over the place on them. My mother would pack us sandwiches and a bottle of water each, and off we would go for the day � to Jack Woods where we had a den with our friends, or to Danson Park (photograph right) to play, or to go swimming in the brand new pool there.

Being a child in those days did have its compensations. We had much more freedom to go out to play. In the school holidays we could go out all day quite safely. We both had scooters and we went all over the place on them. My mother would pack us sandwiches and a bottle of water each, and off we would go for the day � to Jack Woods where we had a den with our friends, or to Danson Park (photograph right) to play, or to go swimming in the brand new pool there. Another favourite place was the children�s playground on the Green (photograph below), built at the same time as Falconwood Parade. It used to have a much higher fence around it with metal spikes at the top. One day I got myself locked in, and had to climb over the fence. I got the back of my dress caught on one of the spikes, and just hung there. All I worried about was showing my knickers, the shame.

Everybody was so thrilled when the Plaza Cinema opened [in 1937] in Blackfen (photograph below) � the pictures played a huge part in my young life. We all went once a week in the evening to see Flash Gordon. It was as big a thrill for the adults as for the children. I�m sure we must have seen other things too, but Flash Gordon made a big impression on me. It was shown as a serial, once a week, so you had to go every week or you missed an episode. Peter and I went on Saturday mornings as well for the children�s programmes � Cowboys and Indians were the favourite.

The noise was deafening, and even worse if the film broke, which it did often in those days. Cat

We used to walk everywhere then; if there were any buses we never used them. My mother did most of her shopping on the Green, which was only a short walk away. All our main groceries were bought at the Co-op, because of the Dividend. The Co-op was very popular with everybody in those days - there was a butchers, a greengrocers, a chemist and the main grocery shop. A large hall over the shop was used for all sorts of functions. My mother belonged to the Co-operative Womens Guild there and I belonged to the youth club, and it was in that hall that I learned to do the �Lambeth Walk�. My dad often sent me to the Co-op to buy him ten cigarettes � no law against serving children with cigarettes then.

Sometimes we would go to Blackfen shopping when we needed something that couldn�t be bought on the Green. My mother was a great knitter, and she bought all her wool at a shop by The Woodman pub, and of course, there was Woolworths. It was an Aladdin�s Cave then, they sold anything and everything, and nothing cost more than sixpence (2.5p). We used to have regular trips to Welling, where we all belonged to the public library. Next door to the library was a baker�s called Rosin�s, and we always had a dozen of their crusty rolls as a special treat.

We didn�t have to go out to the shops for some of the basic necessities. The baker and the milkman called every day. Both drove horse and carts. The baker sold buns and biscuits as well as bread; he carried all his goods in a huge wicker basket and had to keep returning to his horse and cart to fill up again. The milkman called twice a day; he would have started his round very early in the morning, leaving all his customers one pint of milk for the morning tea (no fridges then); he came back mid-morning and people bought more milk and eggs and butter. The fishmonger delivered every Friday.

The garden at 933 played a large part in our lives. There was a trellis right across the garden about two thirds of the way down with a gate in it. Behind this we grew lots of our vegetables and Peter and I played down there a lot, out of sight of the grown ups and within earshot of the Walls ice cream man. He rode a tricycle with a large ice box on the front. In it were vanilla ices that you could have in a cone or in between two wafers; choc ices, my mum and dad�s favourite, and penny Sno Fruits, which were our favourites � these were the same shape as a toblerone, triangular and on a stick; just frozen flavoured ice, but we loved them. The ice cream man rode along the alleyways at the back of the houses ringing his bell and calling �stop me and buy one�; he was very popular.

Every Sunday morning Peter and I went to Sunday school; it wasn�t an option, we had to go. We walked down Crown Woods Way, through Avery Hill Park to the church which was on the other side of the park in Eltham, quite a long walk, and I was in charge of my little brother. We had to wear our best clothes on Sundays: straw hat and white gloves for me, and Peter in his best little suit, tie and cap. I had to keep him out of the ditches somehow, we couldn�t get dirty. This took all morning walking there and back. After we had eaten Sunday dinner, the four of us walked back to Avery Hill Park to listen to the band. Then a visit to the Palm House [the Winter Gardens, photograph left, now part of the University of Greenwich] which was near the bandstand.

Every Sunday morning Peter and I went to Sunday school; it wasn�t an option, we had to go. We walked down Crown Woods Way, through Avery Hill Park to the church which was on the other side of the park in Eltham, quite a long walk, and I was in charge of my little brother. We had to wear our best clothes on Sundays: straw hat and white gloves for me, and Peter in his best little suit, tie and cap. I had to keep him out of the ditches somehow, we couldn�t get dirty. This took all morning walking there and back. After we had eaten Sunday dinner, the four of us walked back to Avery Hill Park to listen to the band. Then a visit to the Palm House [the Winter Gardens, photograph left, now part of the University of Greenwich] which was near the bandstand.

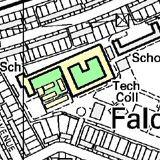

When we first moved in to 933 I went to Days Lane School for a short while, but when Westwood School (map right - click to enlarge) was finished we went there. Westwood was certainly the happiest time of my school life, I loved it there � best of all when I was old enough to go up into the big girls� school (Seniors). It was a lovely building, girls and boys separate, but all in one school. It was built around a grass quad � hallowed ground we were never allowed to set foot on. A corridor ran all the way round the school and looked on to the quad. Halfway on two sides of the corridor were big doors, always locked, to keep the boys from the girls, or the girls from the boys, I�m not sure which, but it worked.

When we first moved in to 933 I went to Days Lane School for a short while, but when Westwood School (map right - click to enlarge) was finished we went there. Westwood was certainly the happiest time of my school life, I loved it there � best of all when I was old enough to go up into the big girls� school (Seniors). It was a lovely building, girls and boys separate, but all in one school. It was built around a grass quad � hallowed ground we were never allowed to set foot on. A corridor ran all the way round the school and looked on to the quad. Halfway on two sides of the corridor were big doors, always locked, to keep the boys from the girls, or the girls from the boys, I�m not sure which, but it worked.

During 1938 when my dad was working at the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane, I met a man who was working with him from the government archives in Ceylon as it was called then. I don�t think I uttered a word as I was so amazed at seeing a black man. However, this man had a daughter the same age as me, and he and my dad arranged an exchange visit for us. This was planned for the summer holidays of the next year � 1939. I was so thrilled, nobody I knew had ever been abroad. Unfortunately the war changed all that and it never took place.

I was twelve in the summer of 1939, and Peter was seven. All through the summer preparations for war were being made. Trenches were dug in all the parks and open spaces for air raid shelters. Everyone had to tape their windows to stop the glass from shattering. We had air raid drill every day at school, filing out in order into the shelters which had been built on the school playing fields.

I was twelve in the summer of 1939, and Peter was seven. All through the summer preparations for war were being made. Trenches were dug in all the parks and open spaces for air raid shelters. Everyone had to tape their windows to stop the glass from shattering. We had air raid drill every day at school, filing out in order into the shelters which had been built on the school playing fields.

Everyone was issued with a gas mask which we had to carry everywhere we went. They were worn over our shoulders like a satchel. Our front room was turned into a �safe room� � quite useless I expect, but it made us feel safer I suppose. The chimney and every crack was stuffed with paper and the windows all sealed. A bowl of water and a blanket were kept in there so we could hang a wet blanket over the door to stop the gas getting in. A supply of tinned food, plus containers of water and a primus stove were also kept in there. I don�t remember that anything was done about sanitary arrangements, so I presume we were supposed to hold our breath while we crept out to the loo. Thank goodness it was never put to the test because gas was never used as a weapon, but at that time it seemed to be the worst fear.

The preparations for war went on. My father joined the LDV (Local Defence Force) which later became the ARP (Air Raid Precautions). He was an air raid warden and was issued with a tin hat, a whistle and an armband. He took all this very seriously, although he was very disappointed that he couldn�t get back into the Navy. Everyone started stocking up with tinned food, my mother always bought extra when she went shopping. Then there was the blackout to prepare for. Blackout curtains were put up in every room in the house. Even my dad�s shed was blacked out.

My father started to work shifts at the Public Record Office. He went to London to work in the morning and came home again on the evening of the next day, then he had a night and a day off. The night he spent at the office he was on firewatching duty. Although the war hadn�t started, everyone had to act as if it had. �Be prepared� was the motto of the time.

Peter and I were allowed to go out as usual, as long as we took our gas masks along.

Looking back on that pre-war period, they were golden days for us. We were quite comfortably off compared with some people. I realise now that we were part of the new elite, living in suburbia in a new house with a large garden. A bedroom each, plenty to eat and �best� clothes as well as school clothes. I suppose our parents must have had their share of worries and troubles the same as any young parents, but we never knew anything about them.

This is an abridged version. The full story, including Pauline's reminiscences of WWII can be found at the Falconwood local history site.

Contributed by Pauline Tookey